Basal Cell and Squamous Cell Skin Cancers

Natural History

Basal cell and squamous cell skin cancers are non-melanoma skin cancers. These cancers are the most common skin cancer forms. More than a million cases/years are diagnosed in the US and incidence is rapidly increasing. BCC is about 4 times as common as squamous cell carcinoma. Basal cell cancers are rarely metastatic and tend to grow by direct extension causing substantial local tissue destruction. NMSC generally have a good prognosis.

Sun exposure is the most significant environmental agent involved in skin cancer development. Fair skinned populations who are overexposed to sunlight are at the greatest risk for these cancers. Most tumors develop in sun exposed sites. Long term survivors of prior radiotherapy are also at increased risk. 95% of basal and squamous cell cancers involve only local disease.

Routes of Spread

Skin cancers have few anatomic barriers to spread along the skin. Fusion planes may limit the depth of invasion, horizontal spread and areas of recurrence of skin cancers, but there is some concern that these embryologic planes persist into adulthood.

The perineural space represents a cleavage plane between a nerve and the nerve sheath and a pathway of decreased resistence to disease spread. Cutaneous nerve "stubs" may be histopathologically involved in both squamous and basal cell carcinomas but larger nerve trunks are less frequently involved. Perineural inflammation with no identifiable perineural disease may be associated with skip mets and more proximal perineural invasion. 60-70% of those with pathologic perineural invasion were assymptomatic. As nerve compression takes place, typical symptoms include anesthesia, paresthesia, muscle weakness diploplia, blindess or stroke. Basal Cell cancers are less frequently involved than squamous cell cancers and more often involve CN V and VII and are typically locally advanced or recurrent in this setting. Squamous cell cancers are much more likely to have PNI at 2.4 - 14% (as opposed to < 1% of BCC).

Squamous Cell cancers with macroscopic or clinically evident nerve involvement are much more likely to have regional and distant metastases. When squamous cell carcinomas involve cranial nerves, (most frequently CN V (trigeminal) and CN VII (facial), there may be significant risk of morbidity and mortality in cases with extension to the skull base and subsequent intracranial spread.

Prognostic and clinical risk factors include tumor location, size, border status and whether tumors are primary or recurrent. In addition immunosuppression and tumors developing in previously irradiation areas are risk factors.

Location is known to be a risk factor for recurrence and metastasis. BCC and SqCC skin cancers that develop in the head and neck are more likely to recur than trunkal or extremity cancers. A "high risk" mask area of the face has been described and proven useful. Sites are divided into high risk, moderate risk and low risk sites based on a NYU study of 5755 people with basal cell cancers treated b curettage and electrodessication.

- Area H: face "mask area"

- central face

- eyelids & brows

- periorbital

- nose

- lips including cutaneous and vermillion

- chin, mandible, pre- & post-auricular region

- temple

- ear

- genetalia

- hands and feet

- Area M: cheeks, forehead, scalp and neck

- Area L: trunk and extremities

Size is also shown to be a risk factor. Most commonly, a size > 2 cm has been used as an adverse prognostic indicator.

Clinical borders and Recurrent Disease. Ill defined borders and recurrence increase risk.

Immunosuppression (organ transplantation and chronic PUVA treatments) significantly increase the risk of developing squamous cell cancers.

When squamous cell carcinoma metastasizes to the regional lymph nodes (usually parotid and cervial), surgery and post-operative radiation therapy provide better loco-regional control than radiation therapy alone. The 5 year survival rate for patients with nodal metastases is 25%. Basal cell and squamous cell distant metastases are usually to the lung, liver and bones.

Staging (AJCC 2010)

| T1 | ≤ 2 cm |

| T2 | > 2 cm or tumor of any size with high risk features |

| T3 | Invasion of maxilla, orbit or temporal bone |

| T4 | Invasion of base of skullor perineural invasion of the skull base |

High risk features include:

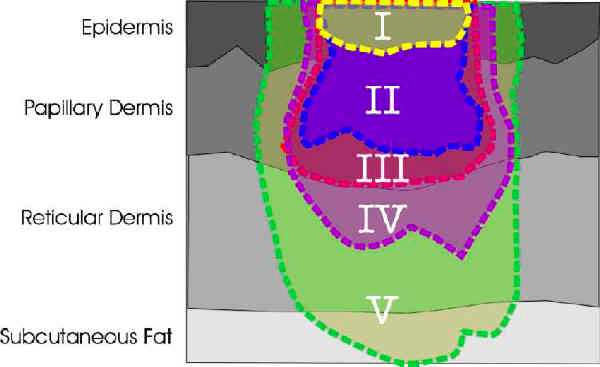

- Depth/Invasion > 2 mm or Clark Level ≥ IV

- Perineural Invasion

- Anatomic Location: Primary site: ear, hair bearing lip

- Differentiation: Poorly differentiated/undifferentiated

Clark Levels:

| N1 | Metastasis in single LN ≤ 3 cm |

| N2a | Metastases in single I/L LN > 3 cm but < 6 cm |

| N2b | Metastases in multiple I/L LN all ≤ 3 cm |

| N2c | Metastases in bilateral or contralateral LN all <el 6 cm |

| N3 | Metastases in bilateral or contralateral LN > 6 cm |

| M0 | No distant mets |

| M1 | Distant Mets |

Stage Grouping

| T | N0 | N1 | N2 | N3 | M1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T1 | I | III | IV | IV | IV |

| T2 | II | III | IV | IV | IV |

| T3 | III | III | IV | IV | IV |

| T4 | IV | IV | IV | IV | IV |

Diagnostic Work Up

A careful history of sun exposure, occupational radiation exposures, immunosuppression, genetics, duration, changes in size or appearnces of skin lesions and prior treatments should be obtained. Symptoms, including neurologic symptoms, physical exam and palpation of lesions should be obtained. Appropriate biopsies are required. A full skin and lymphatic examination should be performed. Lesions of the medial and lateral canthi should be imaged (CT or MRI) as apparently superficial lesions can grow along the wall of the orbit. If perineural invasion is evident, MRI should be used to determine if neural spread exists. Nerve or foramenal involvement may not be apparent until late in the disease course. If there is suspicion that locally advanced disease has invaded bones, a PET/CT may be useful and may offer superior sensitivity and specificity for metastases.

Treatment Options

Most skin cancers can be treated with several therapeutic approaches. Stratification into high risk or low risk should be performed. High risk features include Depth of invasion > 2 mm, perineural invasion (clinical), primary sites: ear or hair bearing lip and poorly differentiated disease.

Sentinel node biopsy's role is not well defined. Metastatic carcinomas may need a combination of treatment modalities for local control and distant control.

- Cryosurgery

- fast and inexpensive

- no therapeutic advantage or cosmetic advantage

- use is considered largely historical

- curettage and electrodessiccation

- not recommended for high-risk or recurrent tumors

- not recommended for areas prone to scar retraction

- not recommended for carcinomas involving scar tissue, cartilage or bone

- surgical excision

- chemotherapy

- photodynamic therapy

- Topical 5FU or imiquimod cream

- Moh's micrographic surgery

- Radiation Therapy

- Primary treatment in age > 50

- Difficult to resect areas such as ear, nasal ala

- Post-op RT in positive margins, PNI, bone, cartilage and muscle invasion

- Parotid area metastases from cutaneous skin cancers.

- Absent data, treatment decisions must be made on a case by case basis.

Radiation Therapy

Studies indicate that one third of BCC that have positive margins ultimately recur, and early recurrences may be difficult to detect, especially in deep margins with fibrosis, or skin graft reconstruction. Patients where close follow up is not possible, immediate re-excision or Moh's surgery or radiation therapy should be considered.

In cases involving a graft, radiation should be delayed until the graft has taken, usually 3 - 4 weeks post operatively. In addition, reasonable dose/fractionation schemes should be used, using a relatively large number of fractions. Recent reports in lung cancer stereotactic treatments indicate that significantly greater microvascular late effects occur at dose of ≥ 10 Gy/fraction. While there is no direct extrapolation to conventional apoptotic doses of 1.8 - 2 Gy/fraction, it is reasonable to assume that higher dose/fractions will injure the developing vasculature in the graft.

The entire graft should be included in the treatment volume.

All BCC with positive margins treated by one group were controlled with radiation. Immediate retreatment, either with surgery or radiation therapy should be performed when a squamous cell carcinoma extends to the margins, due to the high rate of local-regional recurrence.

Doses Recommended for skin cancers:

| Size of Lesion (cm) | Dose/Fraction | HVL | Total Dose | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0.5 - 2.0 cm | 3 Gy | 50 - 150 kVp | 0.7 mm Al - 0.52 mm Cu | 45 - 51 Gy |

| > 2 cm w/o bone involvement |

2.5 Gy | 180 - 300 kVp | 0.87 - 3.7 mm Cu | 50 - 55 Gy |

| 0.5 - 2.0 cm | 6 - 9 MeV (0.5 -1 cm Bolus) | 3.3 Gy | 49.5 - 56 Gy |

| > 2 cm/no bone involvement | 9 - 16 MeV | 2.75 Gy | 55 - 60.5 Gy |

| > 2 cm and bone involvement | 4 - 6 MV photons or 0 - 20 MeV electrons or mixed |

2 Gy | 68 - 72 Gy |

Perineural invasion is controversial. PNI in squamous cell carcinomas is associated with aggressive behavior and radiation therapy is generally recommended. University of Florida studied 135 patients treated with surgery followed by RT, and demonstrated local control rates of 87% and 55% for those with microscopic and macroscopic PNI. Combined modality treatment is generally preferred, although the extent of improvement with RT in microscopic PNI is debated. If PNI is present in head and neck skin cancers, then an MRI should be performed to evaluate the extent of spread to base of skull and regional lymph nodes.

Parotid Area Metastases

Radiation therapy plays an important role in treatment of parotid area metastais from skin cancers. Parotid lymphatics drain most of the face and scalp and are the site most commonly involved when head and neck skin cancer metastasizes to the regional lymphatics. Local control rates of 89% with radiation v. 63% without have been reported and UCSF demonstrated that elective ipsilateral neck radiation decreased the incidence of subsequent nodal failures from 50% to 0%.

Outomes

Previously untreated BCC retrospective series reported 5 year local control of Basal Cell Cancers:

- Excision: 90%

- Radiation: 91%

- Curettage & electrodessication: 92%

- Cryoablation 93%

- Moh's: 99%

For recurrences the 5 year local control rate with radiation is 87% and compares favorably with cryotherapy (< 87%), surgical excision (83%), and C&E (60%).

For eyelid BCC and SqCC treated with radiation therapy LC-5 rates were 95% and 93% respectively. The complication rate was 10% but Fitzpatrick's study of 1166 patients did not differentiate neoplastic damage from treatment related injury. Less than half the complications were considered serious and cosmesis was excellent, as reported in this study.

Toxicity

Radiation doses high enough to eradicate BCC and SqCC will cause moist desquamation. The skin reactions will reach the peak around 2 - 3 weeks into treatment and resolve spontaneously 2 - 6 weeks post radiation completion. Long term cosmetic outcomes are a function of fraction size, total dose, volume of skin irradiated and anatomic location. Radiation affects microvasculature resulting in increased sensitivity to trauma. Surgical wound healing will be slower, with delayed wound healing not uncommon. Hair loss and loss of sweat gland function are usually permanent. Soft tissue necrosis is typically less than 3%. Osteoradionecrosis rates are less than 1% and radiochondritis is rare.

.

.